As a new developer to an open-source project, it can be quite intimidating to figure out where to begin, particularly for your first contribution to the project. And the first step before even doing your first contribution is actually finding that first issue to work on—a task which I’ve found is often underestimated for its difficulty. While there do exist many blog posts on this issue, they tend to begin and end at filtering the list of issues by using the “good first issue” label on GitHub. However, as we will see in the example we’ll walk through, that doesn’t universally work for all open-source projects—and beginners are then left in the dust about what to do next.

My goal with this post is to demonstrate for you how you’re going to be walking through a given open source project to identify a couple of “easy” first issues to work on. I will also walk you through some of the nuances of issues, and importantly the social context of the project, and how these play an important role in navigating your open-source project of choice.

Context and Prerequisites

I wrote this blog post as an adaptation of a lecture segment I’ve given in the Reverse Engineering and Modeling course at UC Irvine with Professor André van der Hoek, where we teach students how to become productive contributors to large, unfamiliar software systems. In fact, we even wrote a paper on that course that appeared in the International Conference on Software Engineering!

So, I’m writing this post for an audience similar to our student cohort in the Professional Master of Software Engineering program—folks who already know how to program, but maybe have not had much experience working in an open-source system. I’m also assuming that you already have an open-source project of choice to work on. (If this is something you need help with, let me know in the comments and I can work on this as a related post!)

The open source project I’m going to be using to walk through is Tensorflow. It’s an open-source library for Deep Learning that is written mostly in C++ and is maintained by Google. If that sounds super scary, don’t worry—I’m using this as the example project mainly because of the abundance of activity the project has so that I can demonstrate various scenarios you may encounter. Even if you are working in a project that is a completely different language or product, all these same tips should still apply.

Why do we need to vet the issues at all?

It seems like so much extra effect to go through all this detective work to find “the best” issue to work on, so why should we even bother? Why not just start coding on the first issue we see?

The biggest reason why we need to actually vet the issues before we begin working on one is because anyone can post an issue to GitHub.

It can be hard, I think, for newcomers to open-source to understand this. When you’re a beginner, its easy to assume that everyone active on the GitHub page is official and knows what they’re doing. Let’s look at a few real, mostly silly examples from the Tensorflow page itself to show you this is definitely not the case:

Bad Issue Example 1: An Angry Customer

Here’s an example that made me chuckle. This individual is demanding “1st class windows support” be provided. This is obviously an example of something that cannot actually be coded up in the scope of a simple GitHub issue, but perhaps was an individual airing their greivances in a misguided forum. Maybe instead of GitHub, they could have found the TensorFlow customer support page?

Bad Issue Example 2: Red Alert! Unrelated webpage down!

Red alert! The personal webpage for a professor is DOWN!

Now, I’m not being entirely fair putting this in the bad issue section. For context, Yann LeCun is a professor of Computer Science, and he is one of the original creators of the MNIST database, which is an important database that TensorFlow gives their users access to. At least as of this writing, there are examples of TensorFlow’s official documentation pointing to the dataset hosted on Professor LeCun’s webpage.

Despite the relevancy of this webpage to the TensorFlow project, this is not a good example of an issue you’d want to find yourself blindly working on as a newcomer to the project. How would someone even go about fixing this without access to LeCun’s webpage code? This is a good one to leave to the project maintainers to figure out.

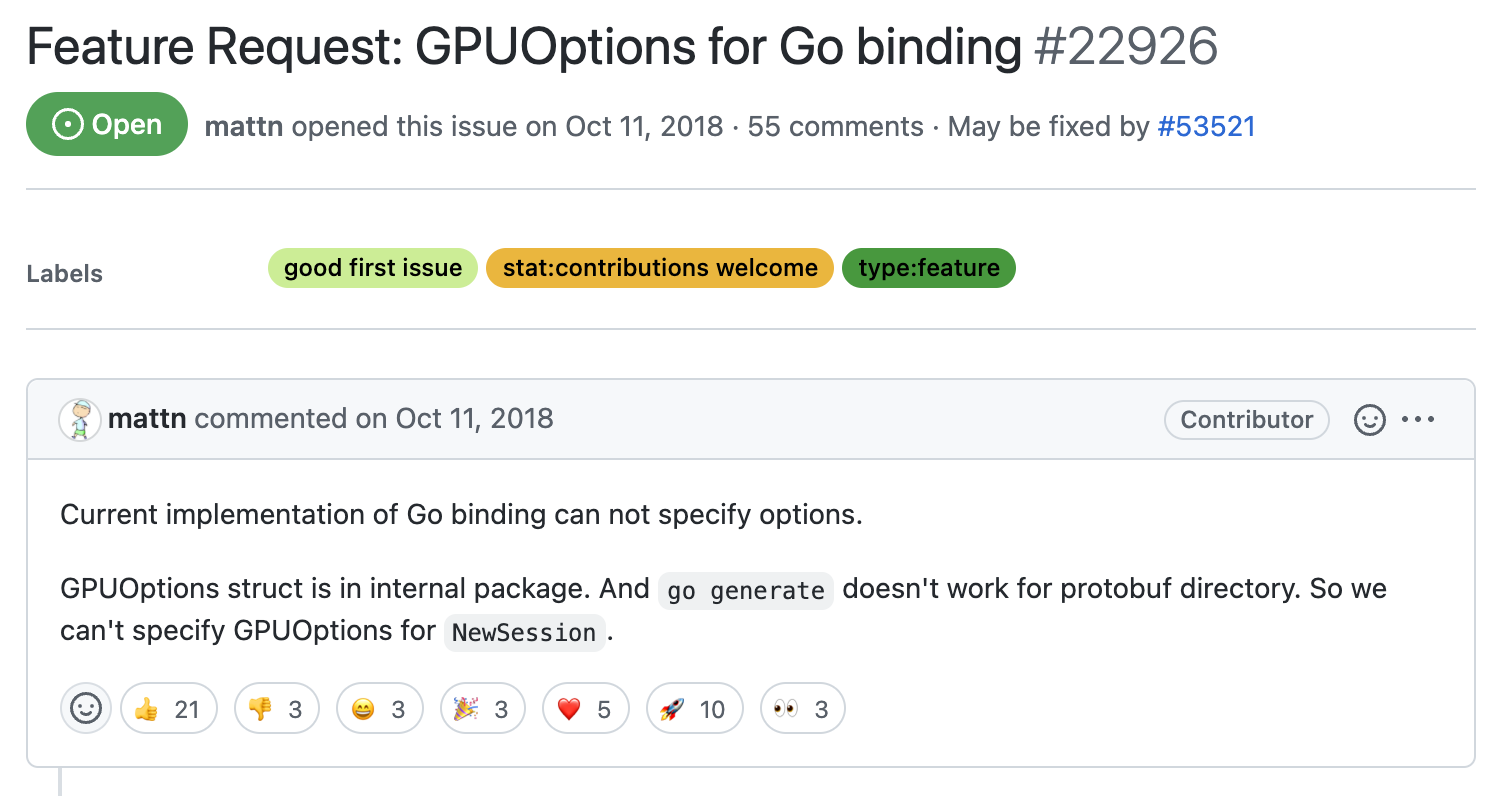

Bad Issue Example 3: “Good First Issue” that is actually mega-hard

At first glance, its not really obvious why this issue belongs in this list. This issue (as of the time of writing), is actually still open on the TensorFlow page. For an issue to be open for nearly 4 years is almost unheard of in the fast-paced world of open-source.

As we scroll down perusing the comments on this issue, we find lots of moderators and experienced developers trying to gain more context about how to both understand and reproduce the issue—a critical component we’ll discuss more later on.

About halfway through the comments, we stumble upon a comment from a user @Gomesz785 that aptly summarizes the theme here:

Silly examples aside, this is actually my favorite example because it really drives home the true reason why we can’t always just “trust” minimal filtering of issues.

Summary

So, to summarize, here’s why it’s not the best idea to grab the first issue we see on the project:

- Anyone can post an issue

- Big projects like on Tensorflow have dozens of posts weekly

- Could be that someone just didn’t understand how the feature worked

- Could be some setting on their local machine

- Maybe they didn’t have the proper dependencies installed

- Could be a bug

- Could be a feature request! (generally more work)

A Heuristic to Search for Easy Issues

Ok so there’s a lot of potential reasons why we shouldn’t just grab the first random issue we see. But what is it we do want to be looking for instead? And how can we go about this process?

In this section, I’m going to outline a heuristic for finding a suitable easy issue. I’ll walk through each step/theme in detail with TensorFlow, and then at the bottom I’ll leave an action-item you can try in your chosen open-source system alongside.

Documentation: The Information Kiosk of Open-Source

I like to think of documentation in an open-source GitHub project as the equivalent of the Information Kiosk or Customer Service desk. This is the easy, no-brainer, first-stop we’re going to to get some information. Are they always 100% right? Certainly not, we can all think of examples where Customer Service has given us well-intended, but ultimately misguided information about how to proceed on a given topic. But usually, the Information Kiosk is going to have the latest company-provided information on a variety of different topics.

In TensorFlow, and in many open-source projects, the guidelines for contributors can be found in a doc titled CONTRIBUTING.md. Taking a look at the below snippet from the Contribution doc for TensorFlow:

If you want to contribute, start working through the TensorFlow codebase, navigate to the Github “issues” tab …start by trying one of the smaller/easier issues here i.e. issues with the “good first issue” label and then take a look at the issues with the “contributions welcome” label.

But, when we go to the Issues tab for TensorFlow and search by “Good First Issue”, we are actually only left with one issue, and this is the same god-level issue we talked about above.

So, unfortunately, for TensorFlow, our Information Kiosk was not particularly trustworthy on this topic. One of the most important things you’ll learn from working on enough open-source, is that the code is always the ultimate source of truth. Documentation is nice, sometimes it looks really official, but it is subject to being out-of-date or flat-out wrong.

Action Item: For your open source project: go ahead and try this first step. Look at the documentation for Contributors, and if they suggest that you look at issues by the common “Good First Issue” or “Contributions Welcome” labels, go ahead and actually try filtering the Issues with these. Take note of what is left, and whether its several issues, or not many at all like in this case.

- When applying this in Tensorflow, here’s what we have.

Easy Bugs: The White Whale of Open-Source Issues

Fundamentally, what we’re really looking for when we’re trying to find an “easy first issue”, is actually an “easy bug.”

Why not Features?

Generally, we’re going to want to avoid features at this point. If its your very first contribution, bug fixes are generally going to be less involved, require less familiarity with the code base, and will be a great way to gain expertise in your given project. Working on a Feature would be a great goal for a second or third contribution later on!

What makes a bug an “easy bug”?

An “easy bug” does not necessarily mean that its easy to fix. In this context, an easy bug means the following:

- Specific: Usually in the official formatting as outlined in the documentation of the repository

- Reproducible: We have precise steps outlined for us to reproduce this issue on our own machine

- Some official recognition from admins: Shows that someone else has been able to reproduce the issue on their own machine

So, an “easy bug” in this case is really easy to spot and reproduce on your machine. How difficult it actually is to fix is something that you can try to decipher by reading the comments for the given issue, and mostly by working on the bug itself.

A quick and dirty way to find bugs is to simply use the label for it in GitHub. Usually, its titled “Bugs”, or something like that. In TensorFlow, its actually titled “type:bug.”

Now, this will filter all the issues just categorized as “bug”, but they are certainly not automatically meeting the criteria of an “easy bug” listed above. I call it a “white whale” because for it to meet all of these criteria can actually be quite rare.

In TensorFlow, here’s an example of a bug that meets our criteria of an “easy bug.”

Action Item: In your open-source project issues list from above, now apply the label “Bugs” (or whatever the equivalent is in your project) and see what you’re left with. We’re going to narrow down this list further in the next step, so don’t filter out by “easy bugs” just quite yet.

- Since the list from TensorFlow above only contained 1 issue, I’m going to clear those two “good first issue” and “contributions welcome” labels. Applying only the “type:bugs” label, here’s what we have for TensorFlow at this point.

Releases: The Fountain of Youth

There’s a lot of issues in a given GitHub project that are inevitably out-of-date. Even if we do find our precious Easy Bug, how can we tell which ones are still relevant to us?

The quick and easy answer to this: look at the latest Release. For any open-source project, the latest Release contains the most recent version of the project’s code.

The reason that the latest release is going to be the best place to look for bugs essentially comes down to the Reproducible criteria we discussed above for Easy Bugs. Even if we have a perfectly outlined bug, if all the instructions for reproducing that bug are related to code from 7 releases ago, how can we be sure this is still relevant? By grabbing issues that are related to the latest release, we can be sure that the information provided with it and the code we write are going to be most relevant to the current state of the project.

For TensorFlow, and many projects on GitHub, there should be a /releases pages we can look at. Here’s the Release page for TensorFlow, where we can find the number of the latest release. Usually its going to be some number with decimals.

In TensorFlow, they actually have labels for each release. We find the label corresponding with the latest release number to further filter our issues.

Action Item: Depending on the conventions of the project you’re working on, there could be several different ways we can filter issues by the release.

- One way, if its like TensorFlow, is through labels. If this is the case, simply find the label corresponding to the most recent release, and filter your list even further.

- If your project does not use Labels corresponding to the Release on the Issues page, try digging around your project documentation to see if there is a way that they separate out issues with the corresponding Release.

- If all else fails, look at the date of the latest release on the Releases page of your project. Then, look at issues only posted after this date.

- For TensorFlow, here’s our filtered list at this point. This is pretty incredible, we started with over 2,000 open issues, and we’ve filtered it down to just 6!

And finally, the moment we’ve all been waiting for!

At this point in the process, if you’ve been following along with the Action Items at the end of each heuristic, you should have a much more manageable list of Issues left. At this point, with the issues you have left, you’re going to want to more carefully apply the criteria for an Easy Bug we discussed above. As long as you find something that mostly meets this criteria, you should be good to go ahead and start actually coding on this!

Parting Advice

Remember, this is a heuristic—its not meant to be an exact replica of steps you can duplicate for any open-source system. There might be things you have to tweak—for instance, you might have to include the latest few releases, instead of just the latest one in order to find an appropriate open issue to work on.

One of my favorite experts on the practice, Joshua Bloch, aptly puts it:

“Learning the art of programming, like most other disciplines, consists of first learning the rules and then learning when to break them.”

So, hopefully these general steps will give you a much more thorough and nuanced outline in order to start contributing to your open-source system, but they will not ever be a 100% exact process to duplicate.

If you enjoyed this post, have ideas for a future topic, or want me to dive deeper on any of the topics discussed above, please comment below and let me know!

Read on Medium →